Background

12

Angry Men (1957), or Twelve Angry Men (1957), is the

gripping, penetrating, and engrossing examination of a diverse

group of twelve jurors (all male, mostly middle-aged, white, and

generally of middle-class status) who are uncomfortably brought

together to deliberate after hearing the 'facts' in a seemingly

open-and-shut murder trial case. They retire to a jury room to

do their civic duty and serve up a just verdict for the indigent

minority defendant (with a criminal record) whose life is in the

balance. The film is a powerful indictment, denouncement and expose

of the trial by jury system. The frightened, teenaged defendant

is on trial, as well as the jury and the American judicial system

with its purported sense of infallibility, fairness and lack of

bias. 12

Angry Men (1957), or Twelve Angry Men (1957), is the

gripping, penetrating, and engrossing examination of a diverse

group of twelve jurors (all male, mostly middle-aged, white, and

generally of middle-class status) who are uncomfortably brought

together to deliberate after hearing the 'facts' in a seemingly

open-and-shut murder trial case. They retire to a jury room to

do their civic duty and serve up a just verdict for the indigent

minority defendant (with a criminal record) whose life is in the

balance. The film is a powerful indictment, denouncement and expose

of the trial by jury system. The frightened, teenaged defendant

is on trial, as well as the jury and the American judicial system

with its purported sense of infallibility, fairness and lack of

bias.

Alternatively, the slow-boiling film could also be

viewed as commentary on McCarthyism, Fascism, or Communism (threatening

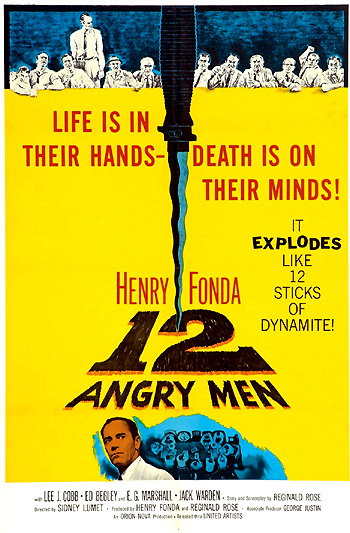

forces in the 50s). One of the film's posters described how the

workings of the judicial process can be disastrous:

"LIFE IS IN THEIR HANDS - DEATH IS ON THEIR MINDS! It EXPLODES

Like 12 Sticks of Dynamite."

This was live television-trained director Sidney Lumet's

first feature film - a low-budget ($350,000) film shot in only 19

days from a screenplay by Reginald Rose, who based his script on

his own teleplay of the same name. After the initial airing of the

TV play in early 1954 on Studio One CBS-TV, co-producer/star Henry

Fonda asked Rose in 1956 if the teleplay could be expanded to feature-film

length (similar to what occurred to Paddy Chayefsky's TV play Marty

(1955)), and they became co-producers for the project (Fonda's

sole instance of film production).

The jury of twelve 'angry men,' entrusted with the

power to send an uneducated, teenaged Puerto Rican, tenement-dwelling

boy to the electric chair for killing his father with a switchblade

knife, are literally locked into a small, claustrophobic rectangular

jury room on a stifling hot summer day until they come up with a

unanimous decision - either guilty or not guilty. The compelling,

provocative film examines the twelve men's deep-seated personal prejudices,

perceptual biases and weaknesses, indifference, anger, personalities,

unreliable judgments, cultural differences, ignorance and fears,

that threaten to taint their decision-making abilities, cause them

to ignore the real issues in the case, and potentially lead them

to a miscarriage of justice.

Fortunately, one brave dissenting juror votes 'not

guilty' at the start of the deliberations because of his reasonable

doubt. Persistently and persuasively, he forces the other men to

slowly reconsider and review the shaky case (and eyewitness testimony)

against the endangered defendant. He also chastises the system for

giving the unfortunate defendant an inept 'court-appointed' public

defense lawyer who "resented being appointed"

- a case with "no money, no glory, not even much chance of winning"

- and who inadequately cross-examined the witnesses. Heated discussions,

the formation of alliances, the frequent re-evaluation and changing

of opinions, votes and certainties, and the revelation of personal

experiences, insults and outbursts fill the jury room.

[Note: A few of the film's idiosyncracies: Even

in the 50s, it would have been unlikely to have an all-male, all-white

jury. However, it's slightly forgivable since the play made the

jury and trial largely symbolic and metaphoric (the jurors were

made to represent a cross-section of American attitudes towards

race, justice, and ideology, and were not entirely realistic.)

The introduction of information about the defendant's past juvenile

crimes wouldn't have been allowed. Jurors # 3 and # 10 were so

prejudiced that their attitudes would have quickly eliminated them

from being selected during jury review. And it was improper for

Juror # 8 to act as a defense attorney - to re-enact the old man's

walk to the front door or to investigate on his own by purchasing

a similar knife. The 'angry' interactions between some of the jurors

seem overly personal and exaggerated.]

This classic, black and white film has been accused

of being stagey, static and dialogue-laden. It has no flashbacks,

narration, or subtitles. The camera is essentially locked in the

enclosed room with the deliberating jurors for 90 of the film's 95

minutes, and the film is basically shot in real-time in an actual

jury room. Cinematographer Boris Kaufman, who had already demonstrated

his on-location film-making skill in Elia Kazan's On

the Waterfront (1954) in Hoboken, and Baby

Doll (1956) in Mississippi, uses diverse camera angles (a

few dramatic, grotesque closeups and mostly well-composed medium-shots)

to illuminate and energize the film's cramped proceedings. Except

for Henry Fonda, the ensemble character actors were chosen for their

experience in the burgeoning art of television.

The film was a financial disaster when it first opened

(during a time of colorful widescreen film offerings), but it did

receive three Academy Award nominations (with no wins): Best Picture,

Best Director, and Best Adapted Screenplay. All three categories

lost to David Lean's Oscar-sweeping, extravagant epic film The

Bridge on the River Kwai. Henry Fonda's central role as a

juror with resolute caution was un-nominated as Best Actor.

None of the jurors are named, and they don't formally

introduce themselves to each other (except for two of them in the

final brief ending). Jurors are labeled with numbers based on their

jury numbers and seats at a conference table in the jury room (in

clock-wise order).

The Twelve Jurors:

A summary of the anonymous characters helps to flesh

out their characters and backgrounds. The order in which each eventually

decides to vote "not guilty" is given in brackets:

|

Jurors

|

Description

|

Order of Deciding 'Not Guilty' Verdict

|

Juror #1:

(The Foreman)

(Martin Balsam)

|

A high-school assistant head coach, doggedly concerned

to keep the proceedings formal and maintain authority; easily

frustrated and sensitive when someone objects to his control;

inadequate for the job as foreman, not a natural leader and over-shadowed

by Juror # 8's natural leadership |

[9]

|

Juror #2:

(John Fiedler)

|

A wimpy, balding bank clerk/teller, easily persuaded,

meek, hesitant, goes along with the majority, eagerly offers

cough drops to other men during tense times of argument; better

memory than # 4 about film title |

[5]

|

Juror #3:

(Lee J. Cobb) |

Runs a messenger service (the "Beck and Call" Company),

a bullying, rude and husky man, extremely opinionated and biased,

completely intolerant, forceful and loud-mouthed, temperamental

and vengeful; estrangement from his own teenaged son causes him

to be hateful and hostile toward all young people (and the defendant);

arrogant, quick-angered, quick-to-convict, and defiant until

the very end |

[12]

|

Juror #4:

(E. G. Marshall) |

Well-educated, smug and conceited, well-dressed

stockbroker, presumably wealthy; studious, methodical, possesses

an incredible recall and grasp of the facts of the case; common-sensical,

dispassionate, cool-headed and rational, yet stuffy and prim;

often displays a stern glare; treats the case like a puzzle to

be deductively solved rather than as a case that may send the

defendant to death; claims that he never sweats |

[10-11 - tie]

|

Juror #5:

(Jack Klugman) |

Naive, insecure, frightened, reserved; grew up

in a poor Jewish urban neighborhood and the case resurrected

in his mind that slum-dwelling upbringing; a guilty vote would

distance him from his past; nicknamed "Baltimore" by

Juror # 7 because of his support of the Orioles |

[3]

|

Juror #6:

(Edward Binns) |

A typical "working man,"

dull-witted, experiences difficulty in making up his own mind, a

follower; probably a manual laborer or painter; respectful of

older juror and willing to back up his words with fists |

[6]

|

Juror #7:

(Jack Warden) |

Clownish, impatient salesman (of marmalade the

previous year), a flashy dresser, gum-chewing, obsessed baseball

fan who wants to leave as soon as possible to attend evening

game; throws wadded up paper balls at the fan; uses baseball

metaphors and references throughout all his statements (he tells

the foreman to "stay in there and pitch"); lacks complete

human concern for the defendant and for the immigrant juror;

extroverted; keeps up amusing banter and even impersonates James

Cagney at one point; votes with the majority |

[7]

|

Juror #8:

(Henry Fonda) |

An architect, instigates a thoughtful reconsideration

of the case against the accused; symbolically clad in white;

a liberal-minded, patient truth-and-justice seeker who uses soft-spoken,

calm logical reasoning; balanced, decent, courageous, well-spoken

and concerned; considered a do-gooder (who is just wasting others'

time) by some of the prejudiced jurors; named Davis |

[1]

|

Juror #9:

(Joseph Sweeney) |

Oldest man in group, white-haired, thin, retiring

and resigned to death but has a resurgence of life during deliberations;

soft-spoken but perceptive, fair-minded; named McCardle |

[2]

|

Juror #10:

(Ed Begley) |

A garage owner, who simmers with anger, bitterness,

racist bigotry; nasty, repellent, intolerant, reactionary and

accusative; segregates the world into 'us' and 'them'; needs

the support of others to reinforce his manic rants |

[10-11 - tie]

|

Juror #11:

(George Voskovec) |

A watchmaker, speaks with a heavy accent, of German-European

descent, a recent refugee and immigrant; expresses reverence

and respect for American democracy, its system of justice, and

the infallibility of the Law |

[4]

|

Juror #12:

(Robert Webber) |

Well-dressed, smooth-talking business ad man with

thick black glasses; doodles cereal box slogan and packaging

ideas for "Rice Pops"; superficial, easily-swayed,

and easy-going; vacillating, lacks deep convictions or belief

system; uses advertising talk at one point: "run this idea

up the flagpole and see if anybody salutes it" |

[8]

|

Plot Synopsis

The film opens with the camera looking up at the imposing

pillars of justice outside Manhattan's Court of General Sessions

on a summer afternoon. The subjective camera wanders about inside

the marbled interior rotunda and hallways, and on the second floor

haphazardly makes its way into a double-doored room marked 228. There,

a bored-sounding, non-committal judge (Rudy Bond) wearily instructs

the twelve-man jury to begin their deliberations after listening

to six days of a "long and complex case of murder in the first

degree." He admonishes them that it is a case involving the

serious charge of pre-meditated murder with a mandatory death sentence

upon a guilty verdict, and now it is the jury's duty to "separate

the facts from the fancy" because "one man is dead" and "another

man's life is at stake."

The judge states the important criteria for judgment

regarding "reasonable doubt," as the camera pans across

the serious faces of the jury members:

If there's a reasonable doubt in your minds as to

the guilt of the accused, a reasonable doubt, then you must bring

me a verdict of not guilty. If however, there is no reasonable

doubt, then you must in good conscience find the accused guilty.

However you decide, your verdict must be unanimous. In the event

that you find the accused guilty, the bench will not entertain

a recommendation for mercy. The death sentence is mandatory in

this case. You are faced with a grave responsibility. Thank you,

gentlemen.

As the jury leaves the box and retires to the jury

room to deliberate, the camera presents a side-view and then a lingering,

silent closeup of the innocent-faced, frightened, despondent slum

boy defendant with round, sad brown eyes. [His ethnicity, whether

he's Puerto Rican or Hispanic, is unspecified.] The plaintiff musical

theme of the film (a solo flute tune by Kenyon Hopkins) plays as

the claustrophobic, bare-walled, stark jury room (with a water cooler

in the corner and a dysfunctional mounted wall fan) dissolves into

view - and the credits are reviewed. |