|

Innovations Necessary for the Advent of Cinema:

Optical toys, shadow shows, 'magic lanterns,' and visual

tricks have existed for thousands of years. Many inventors, scientists,

and manufacturers have observed the visual phenomenon

that a series of individual still pictures set into motion created

the illusion of movement - a concept termed persistence of vision.

This illusion of motion was first described by British physician Peter

Mark Roget in 1824, and was a first step in the development of the

cinema.

A number of technologies, simple optical toys and mechanical inventions related to motion

and vision were developed in the early to late 19th century that were

precursors to the birth of the motion picture industry:

- [A very early version of a "magic lantern"

was suggested in the mid-17th century by German Jesuit priest

Athanasius Kircher in Rome. However, the official inventor

of a usable device was prominent Dutch astronomer/scientist

Christiaan Huygens in the 1650s. Like a modern slide projector

(which has since gone out of date!), its main feature was a

lens that projected images from transparencies onto a screen,

with a simple light source (such as a candle).]

- 1824 - the invention of the Thaumatrope (the

earliest version of an optical illusion toy that exploited the concept

of "persistence of vision" first presented by Peter Mark Roget in a scholarly article) by an English doctor named Dr. John Ayrton Paris

- ca. 1826 or 1827 - the oldest recorded

(and surviving) permanent photograph made in a camera was taken

by French inventor Joseph Nicéphore Niépce. He used

a camera obscura device which captured and projected a

scene illuminated by sunlight. The photo image was "shot" at his

estate named Le Gras from his studio's upstairs window in the Burgundy

region of France in the early 1820s. It

was a very rudimentary photograph (using principles of lithography)

- the image is now known as View

from the Window at Le Gras. His invention was called heliography,

or "light

writing."

- 1831 - the discovery of the law of electromagnetic

induction by English scientist Michael Faraday, a principle used

in generating electricity and powering motors and other machines (including

film equipment)

- 1832 - the invention of the Fantascope (also

called Phenakistiscope or "spindle viewer") by

Belgian inventor Joseph Plateau, a pre-film animation tool

that simulated motion. A series or sequence of separate pictures

depicting stages of an activity, such as juggling or dancing,

were arranged around the perimeter or edges of a slotted disk.

When the disk was placed before a mirror and spun or rotated,

a

spectator

looking through the slots 'perceived' a moving picture. spectator

looking through the slots 'perceived' a moving picture.

- 1834 - the invention and patenting of another stroboscopic device adaptation, the Daedalum (renamed the Zoetrope

in 1867 by American William Lincoln) by British inventor William George

Horner. It was a hollow, rotating drum/cylinder with a crank, with a

strip of sequential photographs, drawings, paintings or illustrations on the interior surface and regularly

spaced narrow slits through which a spectator observed the 'moving' drawings.

- 1839 - the birth of still photography with the development

of the first commercially-viable daguerreotype (a method

of capturing still images on silvered, copper-metal plates) by

French painter and inventor Louis-Jacques-Mande Daguerre, following

on the work of Joseph Nicéphore Niépce. It was the

first commercially-available, mass-market means of taking photographs.

- 1841 - the patenting of calotype (or Talbotype,

a process for printing negative photographs on high-quality paper) by

British inventor William Henry Fox Talbot

- 1861 - the invention of the Kinematoscope, patented by Philadelphian Coleman Sellers, an improved rotating paddle machine to view (by hand-cranking) a series of stereoscopic still pictures on glass plates that were sequentially mounted in a cabinet-box

- 1869 - the development of celluloid by John

Wesley Hyatt, patented in 1870 and trademarked in 1873 - later used

as the base for photographic film

- 1870 - the first demonstration of the Phasmotrope (or Phasmatrope) by Henry Renno Heyl in Philadelphia, that showed a rapid succession of still or posed photographs of dancers, giving the illusion of motion

- 1877 - the invention of the Praxinoscope by

French inventor Charles Emile Reynaud - it was a 'projector' device

with a mirrored drum that created the illusion of movement with picture

strips, a refined version of the Zoetrope with mirrors at the center

of the drum instead of slots; public demonstrations of the Praxinoscope

were made by the early 1890s with screenings of 15 minute 'movies' at

his Parisian Theatre Optique

- 1879 - Thomas Alva Edison's first public exhibition

of an efficient incandescent light bulb, later used for film projectors

Late 19th Century Inventions and Experiments: Muybridge, Marey, Le

Prince and Eastman

Pioneering

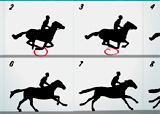

Britisher Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904), an early photographer and inventor,

was famous for his photographic loco-motion studies (of animals and humans)

at the end of the 19th century (such as 1882's published "The Horse in Motion").

In the 1870s, Muybridge experimented with instantaneously recording the movements of a galloping horse, first at a Sacramento (California) race track. In June, 1878, he successfully conducted a 'chronophotography' experiment

in Palo Alto (California) for his wealthy San Francisco benefactor, Leland Stanford, using a multiple series of cameras

to record a horse's gallops - this conclusively proved that all four of the horse's feet were off the ground at the same time. Pioneering

Britisher Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904), an early photographer and inventor,

was famous for his photographic loco-motion studies (of animals and humans)

at the end of the 19th century (such as 1882's published "The Horse in Motion").

In the 1870s, Muybridge experimented with instantaneously recording the movements of a galloping horse, first at a Sacramento (California) race track. In June, 1878, he successfully conducted a 'chronophotography' experiment

in Palo Alto (California) for his wealthy San Francisco benefactor, Leland Stanford, using a multiple series of cameras

to record a horse's gallops - this conclusively proved that all four of the horse's feet were off the ground at the same time.

Muybridge's pictures, published widely in the late 1800s, were often

cut into strips and used in a Praxinoscope, a descendant of the

zoetrope device, invented by Charles Emile Reynaud in 1877. The

Praxinoscope was the first 'movie machine' that could project a

series of images onto a screen. Muybridge's stop-action series of photographs

helped lead to his own 1879 invention of the Zoopraxiscope (or

"zoogyroscope", also called the "wheel of life"), a primitive motion-picture projector machine

that also recreated the illusion of movement (or animation) by projecting

images - rapidly displayed in succession - onto a screen from photos printed

on a rotating glass disc. Muybridge's pictures, published widely in the late 1800s, were often

cut into strips and used in a Praxinoscope, a descendant of the

zoetrope device, invented by Charles Emile Reynaud in 1877. The

Praxinoscope was the first 'movie machine' that could project a

series of images onto a screen. Muybridge's stop-action series of photographs

helped lead to his own 1879 invention of the Zoopraxiscope (or

"zoogyroscope", also called the "wheel of life"), a primitive motion-picture projector machine

that also recreated the illusion of movement (or animation) by projecting

images - rapidly displayed in succession - onto a screen from photos printed

on a rotating glass disc.

True motion pictures, rather than eye-fooling 'animations', could only

occur after the development of film (flexible and transparent celluloid)

that could record split-second pictures. Some of the first experiments

in this regard were conducted by Parisian innovator and physiologist Etienne-Jules

Marey in the 1880s. He was also studying, experimenting, and recording

bodies (most often of flying animals, such as pelicans in flight) in motion using photographic means (and French astronomer Pierre-Jules-Cesar Janssen's "revolving photographic plate" idea). True motion pictures, rather than eye-fooling 'animations', could only

occur after the development of film (flexible and transparent celluloid)

that could record split-second pictures. Some of the first experiments

in this regard were conducted by Parisian innovator and physiologist Etienne-Jules

Marey in the 1880s. He was also studying, experimenting, and recording

bodies (most often of flying animals, such as pelicans in flight) in motion using photographic means (and French astronomer Pierre-Jules-Cesar Janssen's "revolving photographic plate" idea).

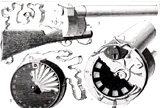

In 1882, Marey, often

claimed to be the 'inventor of cinema,' constructed a camera (or "photographic

gun") that could take multiple (12) photographs per second of moving

animals or humans - called chronophotography or serial photography, similar to Muybridge's work on taking multiple exposed images of running horses. [The term shooting

a film was possibly derived from Marey's invention.] He was able to

record multiple images of a subject's movement on the same camera plate,

rather than the individual images Muybridge had produced. In 1882, Marey, often

claimed to be the 'inventor of cinema,' constructed a camera (or "photographic

gun") that could take multiple (12) photographs per second of moving

animals or humans - called chronophotography or serial photography, similar to Muybridge's work on taking multiple exposed images of running horses. [The term shooting

a film was possibly derived from Marey's invention.] He was able to

record multiple images of a subject's movement on the same camera plate,

rather than the individual images Muybridge had produced.

Marey's chronophotographs (multiple exposures on single glass plates

and on strips of sensitized paper - celluloid film - that passed

automatically through a camera of his own design) were revolutionary.

He was soon able to achieve a frame rate of 30 images. Further experimentation

was conducted by French-born Louis Aime Augustin Le Prince in 1888. Le

Prince used long rolls of paper covered with photographic emulsion for

a camera that he devised and patented. Two short fragments survive of

his early motion picture film (one of which was titled Traffic Crossing

Leeds Bridge).

The work of Muybridge, Marey and Le Prince laid

the groundwork for the development of motion picture cameras,

projectors and transparent celluloid film - hence the development

of cinema. American inventor George Eastman, who had first manufactured

photographic dry plates in 1878, provided a more stable type

of celluloid film with his concurrent developments in 1888 of

sensitized paper roll photographic film (instead of metal or

glass plates) and a convenient "Kodak" small box camera

(a still camera) that used the roll film. He improved upon the

paper roll film with another invention in 1889 - perforated celluloid (synthetic

plastic material coated with gelatin)

roll-film with photographic, light-sensitive emulsion, and sprocket

holes along the sides.

The Birth of US Cinema:

Thomas Edison and William K.L. Dickson

In

the late 1880s, famed American inventor Thomas Alva Edison (1847-1931)

(and his young British assistant William Kennedy Laurie Dickson

(1860-1935)) in his industrial-research laboratories in West Orange,

New Jersey, borrowed from the earlier work of Muybridge, Marey,

Le Prince and Eastman. Their goal was to construct a device for

recording movement on film, and another device for viewing the

film. Dickson must be credited with most of the creative and innovative

developments - Edison only provided the research program and his

laboratories for the revolutionary work. In

the late 1880s, famed American inventor Thomas Alva Edison (1847-1931)

(and his young British assistant William Kennedy Laurie Dickson

(1860-1935)) in his industrial-research laboratories in West Orange,

New Jersey, borrowed from the earlier work of Muybridge, Marey,

Le Prince and Eastman. Their goal was to construct a device for

recording movement on film, and another device for viewing the

film. Dickson must be credited with most of the creative and innovative

developments - Edison only provided the research program and his

laboratories for the revolutionary work.

Although Edison is often credited with the

development of early motion picture cameras and projectors, it was Dickson,

in November 1890, who devised a crude, motor-powered camera that could

photograph motion pictures - called a Kinetograph. It was the

world's first motion-picture film camera - heavy and static, and requiring

lots of light. This was one of the major reasons for the emergence

of motion pictures in the 1890s. Edison Studios was formally known

as the Edison

Manufacturing Company (1894-1911), with innovations due largely

to the work of Edison's assistant Dickson in the mid-1890s. The motor-driven

camera was designed to capture movement with a synchronized shutter

and sprocket system (Dickson's unique invention) that could move the

film through the camera by an electric motor. The Kinetograph used

film which was 35mm wide and had sprocket holes to advance the film.

The sprocket system would momentarily pause the film roll before the

camera's shutter to create a photographic frame (a still or

photographic image).

In 1889 or 1890, Dickson filmed his first experimental

Kinetoscope trial or test film, Monkeyshines No. 1 (1889/1890),

the only surviving film from the cylinder kinetoscope, and apparently

the first motion

picture ever produced on photographic film in the United States. It

featured the movement of laboratory assistant Sacco Albanese, filmed

with a system using tiny images that rotated around the cylinder.

Dickson

Greeting (1891), apparently the second film made in the US, was

composed of test footage of William K.L. Dickson himself, bowing, smiling

and ceremoniously taking off his hat. It was a three-second clip. It

was used for one of the first public demonstrations

of motion pictures in the US using the Kinetoscope, presented to the

Federation of Women's Clubs. Dickson

Greeting (1891), apparently the second film made in the US, was

composed of test footage of William K.L. Dickson himself, bowing, smiling

and ceremoniously taking off his hat. It was a three-second clip. It

was used for one of the first public demonstrations

of motion pictures in the US using the Kinetoscope, presented to the

Federation of Women's Clubs.

In

1891, Dickson also designed an early version of a movie-picture projector

(an optical lantern viewing machine) based on the Zoetrope - called

the

Kinetoscope. It was a peep-show device to allow one person at

a time to watch a 'movie.'

Dickson and Edison also built a vertical-feed motion picture camera in

the summer of 1892. In

1891, Dickson also designed an early version of a movie-picture projector

(an optical lantern viewing machine) based on the Zoetrope - called

the

Kinetoscope. It was a peep-show device to allow one person at

a time to watch a 'movie.'

Dickson and Edison also built a vertical-feed motion picture camera in

the summer of 1892.

The formal introduction of the Kinetograph in October

of 1892 set the standard for theatrical motion picture cameras still

used today. It used a film strip (composed of celluloid coated in

light-sensitive emulsion) that was 1 1/2 inches wide. This established

the basis for today's standard 35 mm commercial film gauge, occurring

in 1897. The 35 mm width with 4 perforations per frame became accepted

as the international standard gauge in 1909. However, moveable hand-cranked

cameras soon became more popular, because the original motor-driven

cameras were heavy and bulky.

On Saturday, April 14, 1894, a refined version of Edison's

Kinetoscope began commercial operation for entertainment purposes.

The floor-standing, box-like viewing device was basically a bulky,

coin-operated, movie "peep

show" cabinet for a single customer (in which the

images on a continuous film loop-belt were viewed in motion as they

were rotated in front of a shutter and an electric lamp-light). It

held 40-50 foot rolls of 'film' - about 16 seconds of viewing time

(of one single, uninterrupted shot). The Kinetoscope, the forerunner

of the motion picture film projector (without sound), was finally patented

on August 31, 1897 (Edison applied for the patent in 1891, granted

in 1893). The viewing device quickly became popular in carnivals, Kinetoscope

parlors, amusement arcades, and sideshows for a number of years.

The

world's first film production studio - or "America's first

movie studio," the Black Maria,

or the Kinetographic Theater (and dubbed "The Doghouse" by

Edison himself), was built on the grounds of Edison's laboratories

at West Orange, New Jersey. Construction

began in December 1892, and it was completed by February 1, 1893,

at a cost of $637.67 (about $16,000 in 2015). It was constructed for

the purpose of making film strips for the Kinetoscope. The interior

walls of the studio were covered with black tar-paper (to make

the performers stand out against the stark black backgrounds).

It had a retractable or hinged, flip-up sun-roof to allow sunlight

in. It was built with a rotating base or turntable (on circular

railroad tracks) to orient itself throughout the day to follow

the natural sunlight. The

world's first film production studio - or "America's first

movie studio," the Black Maria,

or the Kinetographic Theater (and dubbed "The Doghouse" by

Edison himself), was built on the grounds of Edison's laboratories

at West Orange, New Jersey. Construction

began in December 1892, and it was completed by February 1, 1893,

at a cost of $637.67 (about $16,000 in 2015). It was constructed for

the purpose of making film strips for the Kinetoscope. The interior

walls of the studio were covered with black tar-paper (to make

the performers stand out against the stark black backgrounds).

It had a retractable or hinged, flip-up sun-roof to allow sunlight

in. It was built with a rotating base or turntable (on circular

railroad tracks) to orient itself throughout the day to follow

the natural sunlight.

Thomas

Edison displayed 'his' Kinetoscope projector at the World's Columbian

Exhibition in Chicago and received patents for his movie camera, the Kinetograph,

and his electrically-driven peepshow device - the Kinetoscope.

In early May, 1893, Edison also held the world's first public exhibition

or demonstration of films at the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences.

The exhibited 34-second film, Blacksmith

Scene (1893), was viewed on Dickson's Kinetoscope viewer, and

was shot using a Kinetograph at the Black Maria. It showed

three people pretending to be blacksmiths. Thomas

Edison displayed 'his' Kinetoscope projector at the World's Columbian

Exhibition in Chicago and received patents for his movie camera, the Kinetograph,

and his electrically-driven peepshow device - the Kinetoscope.

In early May, 1893, Edison also held the world's first public exhibition

or demonstration of films at the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences.

The exhibited 34-second film, Blacksmith

Scene (1893), was viewed on Dickson's Kinetoscope viewer, and

was shot using a Kinetograph at the Black Maria. It showed

three people pretending to be blacksmiths.

The

first motion pictures made in the Black Maria were deposited for copyright

by Dickson at the Library of Congress in August, 1893. On January 7,

1894, The Edison Kinetoscopic Record of a Sneeze (aka Fred

Ott's Sneeze (1894)) became the first film officially

registered for copyright. It was one of the first series of short

films made by Dickson for the Kinetoscope viewer in Edison's Black

Maria studio with fellow assistant Fred Ott.

The short five-second film was made for publicity purposes, as a series

of still photographs to accompany an article in Harper's Weekly.

It was the earliest surviving, copyrighted motion picture

(or "flicker")

- composed of an optical record (and medium close-up) of

Fred Ott, an Edison employee, sneezing comically for the camera. It

was noted as the first medium-closeup. The

first motion pictures made in the Black Maria were deposited for copyright

by Dickson at the Library of Congress in August, 1893. On January 7,

1894, The Edison Kinetoscopic Record of a Sneeze (aka Fred

Ott's Sneeze (1894)) became the first film officially

registered for copyright. It was one of the first series of short

films made by Dickson for the Kinetoscope viewer in Edison's Black

Maria studio with fellow assistant Fred Ott.

The short five-second film was made for publicity purposes, as a series

of still photographs to accompany an article in Harper's Weekly.

It was the earliest surviving, copyrighted motion picture

(or "flicker")

- composed of an optical record (and medium close-up) of

Fred Ott, an Edison employee, sneezing comically for the camera. It

was noted as the first medium-closeup.

A short film (about 21 seconds long) titled Carmencita

(1894) was directed and produced by Edison's employee William

K.L. Dickson. She was filmed March 10-16, 1894 in Edison's Black

Maria studio in West Orange, NJ. Spanish dancer Carmencita was the

first woman to appear in front of an Edison motion picture camera,

and quite possibly the first female to appear in a US motion picture.

In some cases, the projection of the scandalous film on a Kinetoscope

was forbidden, because it revealed Carmencita's legs and undergarments

as she twirled and danced. This was one of the earliest cases of

censorship in the moving picture industry. A short film (about 21 seconds long) titled Carmencita

(1894) was directed and produced by Edison's employee William

K.L. Dickson. She was filmed March 10-16, 1894 in Edison's Black

Maria studio in West Orange, NJ. Spanish dancer Carmencita was the

first woman to appear in front of an Edison motion picture camera,

and quite possibly the first female to appear in a US motion picture.

In some cases, the projection of the scandalous film on a Kinetoscope

was forbidden, because it revealed Carmencita's legs and undergarments

as she twirled and danced. This was one of the earliest cases of

censorship in the moving picture industry.

Most of the first films shot at the Black Maria included

segments of magic shows, excerpts from stage plays, slapstick comedy,

vaudeville performances (with dancers and strongmen), acrobatics, acts

from Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show and other animal acts, various boxing

matches and cockfights, and scantily-clad women. Most of the earliest

moving images, however, were non-fictional, unedited, crude documentary, "home

movie" views of ordinary

slices of life - street scenes, the activities of police or firemen,

or shots of a passing train. [Footnote: the 'Black Maria' studio appeared

in Universal's comedy Abbott and Costello Meet the Keystone Cops

(1955).]

In the early 1890s, Edison and Dickson also devised a prototype sound-film system called the Kinetophonograph or Kinetophone -

a precursor of the 1891 Kinetoscope with a cylinder-playing phonograph

(and connected earphone tubes) to provide the unsynchronized sound.

The projector was connected to the phonograph with a pulley system,

but it didn't work very well and was difficult to synchronize. It was

formally introduced in 1895, but soon proved to be unsuccessful since

competitive, better synchronized devices were also beginning to appear

at the time. The first known (and only surviving) film with live-recorded

sound made to test the Kinetophone was the 17-second Dickson Experimental

Sound Film (1894-1895). In the early 1890s, Edison and Dickson also devised a prototype sound-film system called the Kinetophonograph or Kinetophone -

a precursor of the 1891 Kinetoscope with a cylinder-playing phonograph

(and connected earphone tubes) to provide the unsynchronized sound.

The projector was connected to the phonograph with a pulley system,

but it didn't work very well and was difficult to synchronize. It was

formally introduced in 1895, but soon proved to be unsuccessful since

competitive, better synchronized devices were also beginning to appear

at the time. The first known (and only surviving) film with live-recorded

sound made to test the Kinetophone was the 17-second Dickson Experimental

Sound Film (1894-1895).

Kinetoscope Parlors and Films Flourish:

On April

14, 1894, the Holland Brothers opened the first Kinetoscope Parlor

at 1155 Broadway in New York City and for the first time,

they commercially exhibited movies, as we know them today, in their

amusement arcade. Each

film cost 5 cents to view. Patrons paid 25 cents as the admission charge

to view films in five kinetoscope machines placed in two rows. The

first commercial presentation of a motion picture took place here.

The mostly male audience was entertained by a single loop reel depicting

clothed female dancers, sparring boxers and body builders (such as Sandow

the Strong Man (1894)), animal acts and everyday scenes. Early

spectators in Kinetoscope parlors were amazed by even the most mundane

moving images in very short films (between 30 and 60 seconds) - an approaching

train or a parade, women dancing, dogs terrorizing rats, and twisting

contortionists. On April

14, 1894, the Holland Brothers opened the first Kinetoscope Parlor

at 1155 Broadway in New York City and for the first time,

they commercially exhibited movies, as we know them today, in their

amusement arcade. Each

film cost 5 cents to view. Patrons paid 25 cents as the admission charge

to view films in five kinetoscope machines placed in two rows. The

first commercial presentation of a motion picture took place here.

The mostly male audience was entertained by a single loop reel depicting

clothed female dancers, sparring boxers and body builders (such as Sandow

the Strong Man (1894)), animal acts and everyday scenes. Early

spectators in Kinetoscope parlors were amazed by even the most mundane

moving images in very short films (between 30 and 60 seconds) - an approaching

train or a parade, women dancing, dogs terrorizing rats, and twisting

contortionists.

Soon, peep show Kinetoscope parlors quickly opened

across the country, set up in penny arcades, hotel lobbies, and

phonograph parlors in major cities across the US. One

of the companies formed to market Edison's Kinetoscopes and the films

was called the Kinetoscope Exhibition Company. It was owned by

Otway Latham, Grey Latham, Samuel Tilden, and Enoch Rector. In the summer

of 1894 in downtown New York City (at 83 Nassau St.), it set up a series

of large-capacity Kinetoscopes (able to handle up to 150 feet of film),

each one showing one, one–minute round of the

six round Michael Leonard-Jack Cushing Prize Fight (1894) film

(produced and filmed at Edison's Black Maria studio). Each viewing

cost 10 cents, or 60 cents to see the entire fight. The popular boxing

film was the first boxing film produced for commercial exhibition.

In June of 1894, pioneering inventor

Charles Francis Jenkins became the first person to project a filmed

motion picture onto a screen for an audience, in Richmond, Indiana,

using his projector termed the Phantoscope. The motion picture

was of a vaudeville dancer doing a butterfly dance - the first motion

picture with color (tinted frame by frame, by hand). Some of the earliest color hand-tinted films ever publically-released were Annabelle

Butterfly Dance (1894), Annabelle Sun Dance (1894), and

Annabelle Serpentine Dance (1895) featuring the dancing of vaudeville-music

hall performer Annabelle Whitford (known as Peerless Annabelle) Moore,

whose routines were filmed at Edison's studio in New Jersey. Male audiences

were enthralled watching these early depictions of a clothed female

dancer (sometimes color-tinted) on a Kinetoscope - an early peep-show

device for projecting short films. In June of 1894, pioneering inventor

Charles Francis Jenkins became the first person to project a filmed

motion picture onto a screen for an audience, in Richmond, Indiana,

using his projector termed the Phantoscope. The motion picture

was of a vaudeville dancer doing a butterfly dance - the first motion

picture with color (tinted frame by frame, by hand). Some of the earliest color hand-tinted films ever publically-released were Annabelle

Butterfly Dance (1894), Annabelle Sun Dance (1894), and

Annabelle Serpentine Dance (1895) featuring the dancing of vaudeville-music

hall performer Annabelle Whitford (known as Peerless Annabelle) Moore,

whose routines were filmed at Edison's studio in New Jersey. Male audiences

were enthralled watching these early depictions of a clothed female

dancer (sometimes color-tinted) on a Kinetoscope - an early peep-show

device for projecting short films.

Young

Griffo v. Battling Charles Barnett (1895) was the first 'movie'

or motion picture in the world to be screened for a paying audience on

May 20, 1895, at a storefront at 156 Broadway in NYC. [This was more

than seven months before the Lumière brothers showed their film

in Paris (see below).] The 8-minute

B&W

silent film (shown on one continuous

reel of film without interruption, using the "Latham Loop" to

prevent tearing) was made by Woodville Latham and his sons Otway and

Grey. The staged boxing match had been filmed with an Eidoloscope Camera

on the roof of Madison Square Garden on May 4, 1895 between Australian

boxer Albert Griffiths (Young Griffo) and Charles Barnett. Shortly

thereafter, nearly 500 people became cinema's first major audience

during the showings of films with titles such as Barber Shop, Blacksmiths, Cock

Fight, Wrestling,

and Trapeze. Edison's

film studio was used to supply films for this sensational new form

of entertainment. More Kinetoscope parlors soon opened in other

cities (San Francisco, Atlantic City, and Chicago).

The Kiss (1896) (aka The May Irwin Kiss) was

the first film ever made of a couple kissing in cinematic history.

May Irwin and John Rice re-enacted a lingering kiss for Thomas Edison's

film camera in this 20-second long short, from their 1895 Broadway

stage play-musical The Widow Jones. It became the most popular

film produced that year by Edison's film company (it was filmed at

Edison's Black Maria studio, in West Orange, NJ), but was also notorious

as the first film to be criticized as scandalous and bringing demands

for censorship. The Kiss (1896) (aka The May Irwin Kiss) was

the first film ever made of a couple kissing in cinematic history.

May Irwin and John Rice re-enacted a lingering kiss for Thomas Edison's

film camera in this 20-second long short, from their 1895 Broadway

stage play-musical The Widow Jones. It became the most popular

film produced that year by Edison's film company (it was filmed at

Edison's Black Maria studio, in West Orange, NJ), but was also notorious

as the first film to be criticized as scandalous and bringing demands

for censorship.

The American Mutoscope Company: Dickson's Split From

Edison

Disgruntled and a disenchanted inventor, William K.L.

Dickson left Edison to form his own company in 1895, called the American

Mutoscope Company (see more further below), the first and

the oldest movie company in America. A nickelodeon film producer who

had been working with Thomas Edison for a number of years, Dickson

left following a disagreement. Three others joined Dickson, inventors

Herman Casler and Henry Marvin, and an investor named Elias Koopman.

The company was set up at 841 Broadway, in New York - its sole focus

was to produce and distribute moving pictures. The business was moved

to Canastota, NY. Superior alternatives to the Kinetoscope were

the company's invention of the Mutoscope -

a hand-cranked viewing device utilizing bromide prints or illustrated

cards in a 'flick-book' principle, and the Biograph projector, released

in the summer of 1896 - a projector using large-format, wide-gauge 68

mm film (different from Edison's 35mm). The Biograph soon

became the chief US competitor to Edison's Kinetoscope and Vitascope.

[Note: The American Mutoscope Company eventually

became the Biograph

Company.]

[By the 1897 patent

date of the Kinetoscope, both the camera (kinetograph) and the method

of viewing films (kinetoscope) were on the decline with the advent

of more modern screen projectors for larger audiences.]

Film History of the Pre-1920s

Film History of the Pre-1920s

Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5

|